On July 26, 2006, 19 year old Jessie Gilbert fell from the 8th floor window of her hotel room in the Czech Republic. Five years ago today, her father was acquitted of repeatedly raping her.

Saturday, October 24, 1998 is a day I remember well. The weather was inclement the whole weekend, and it took me over two hours by public transport to reach the Richmond chess tournament, which wasn’t actually held at Richmond but was the other side of it. This was also the day I met Jessie Gilbert. Although I had returned to chess after a twenty year lay off the year before, and our paths had probably crossed since May 1997, this was the first time I had met her, and as far as I remember, the first time I had seen her. She was a shy young thing, freckled, unobtrusive. We met early on in the tournament, but the game I remember best is the fourth and penultimate round in which I played Timothy Woodward, a fast improving junior.

I’d played and beaten him twice before, and our first game, at Kensington in September 1997, had found its way into the Times the following month. At Richmond he was clearly out for revenge, and playing the black pieces for the third time, I was on the receiving end for the middlegame, and having reached an ending with both of us in desperate time trouble, I had a knight against his bishop and three pawns, but suddenly it was running rampage, and after I sacced my noble horse for his last peon, tournament controller Adam Raoof who was watching the game to make the pairings for the last round, quipped “Play on, play on!”

The game had been ill-tempered throughout – though entirely on his side – and he nearly burst into tears. We ended up joint winners, and I pocketed £75.

If someone had told me after my first game with Jessie that 9 years later to the day she would have stood by my grave and wept, I wouldn’t have been too surprised, nor would I have much cared. If I’d been told instead the boot would be on the other foot, I wouldn’t have taken such a claim seriously.

The following January, Jessie was the highest placed female competitor in the World Amateur Chess Championship at Hastings becoming Women’s World Amateur Champion, the youngest person to win a bona fide adult world title in any discipline. I had played at Hastings the previous year, and although I had scored 4½/11 in the Challengers – a score that is a lot better than it sounds – I had managed only a disappointing 4/11 in what was for me the main event.

Jessie’s achievement – which was neither her first nor her last – thrust her into the limelight in which she would bask for the remainder of her tragically short life.

As her interest in chess waxed, mine waned, as did my ability, although I did win the Crystal Palace Club Championship in Millennium Year, one of my proudest achievements. Jessie drew our fourth game, which she should have won, at Crystal Palace, and won our fifth, which she should not have. The following day I went to the British Library to do some research, and took the scoresheet with me to book up on the line. Unfortunately, I left it there, but I remember the opening well, it was her favourite Caro-Kann.

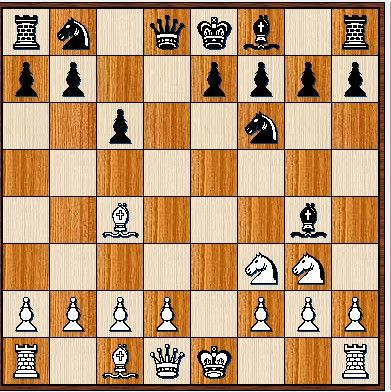

This is from the Two Knights Variation, a slightly off-beat line; I would often play similar lines against juniors to take them out of the book. Her last move, N-B3, or Nf6 if you really must, deserves a double question mark, as does my reply, Ne5. This trap is one that every kibbitzer spots instantaneously, but like the obvious exchange sacrifice on c3 in the Sicilian for example, it is one even master strength players fall into, or leap into, on occasion.

I should have played simply Bxf7+ followed by the knight check recapturing the piece and winning a pawn with a big positional advantage. I didn’t play that because I thought I would have an even bigger advantage after the forced Be6, when Bxe6 fxe6 leaves her position cramped. As things turned out, I played so badly that rather than giving her a cramped position, I allowed her to strengthen her centre.

The finale was comical. We had reached a queen ending where I was a pawn or two down, and noticed my king was stalemated, so sacrificed my queen, to which she replied “That’s not stalemate” or “That’s not a stalemate”. My analysis was brilliant but for one minor but fatal error, my pawn was moving the other way! This game would come back to haunt me in the years ahead.

After our drawn game, on January 24, 2000, Jessie paid me a bizarre compliment, “You’re my Hitler”, she said. After this last encounter, on board 1, I no longer was. For reasons I won’t go into here, I had begun to lose interest in chess or rather, other, darker interests, that had plagued my youth and had nearly been the death of me, came back into my life.

I continued to play for a bit, then just e-mail and the annual Mind Sports Olympiad, but my love affair with Caissa was well and truly over. Then, on the morning of July 26, 2006, I had the shock of my life.

I was beavering away on the computer, when the news on the TV behind me announced that one of Britain’s brightest young chess stars had been killed in an incident abroad. No name was given at that stage, but I went to Google News expecting to read something about either Timothy Woodward or David Howell (whom I had also played), and her name came up.

I remembered when I had first heard or rather saw, the news about 9/11. I had been in the British Library all day, a place I use but rarely nowadays, and on the train home I saw a report on the front page of a newspaper which another passenger was reading. Of course, by the time I got home it was the only event all the news channels were talking about. Although like everyone else I watched re-run after re-run of the Twin Towers collapsing in slow motion experiencing silent fascination, it didn’t affect me anything like as badly as Jessie’s death. There was a very profound reason for that, thirty years earlier, almost to the day, I had woken up covered in vomit after downing four dozen over the counter pain killers washed down with four pints of orange cordial. Like Jessie, I had been a 19 year old chess player. Those were the only things we had in common, or so I thought, though later I realised we shared one other characteristic, a terrible affliction, we had both been delusional.

Shortly after Jessie’s death had been confirmed, another story surfaced, and it didn’t take much to join the dots, her father, Ian Gilbert, was due to stand trial for raping her repeatedly from the age of eight.

I can’t say too much more about this, nor about the other offences for which he stood trial, because in Britain, unlike the US, trials of this nature are conducted if not in camera then with considerable restrictions on their reporting.

I have to say too that if any other girl of her age had made similar allegations against her own father years down the line, I would have been extremely skeptical if not totally dismissive, but Jessie was not any other girl. She was not only highly intelligent, she had an ego the size of a postage stamp. After she won the world title, she had people coming at her from all directions telling her how wonderful she was, yet in all the time I knew her she never changed, she remained the same shy young thing I had first met all those years ago at Richmond. I took her allegations against her father at face value, and I was as disgusted as anyone else at his acquittal, on December 14, 2006. Not only that, the wealthy banker had been on conditional bail throughout.

The following year, I was given unfettered access to Jessie’s personal papers as, among other things, I was writing a book about her. It was while researching these that I came across a document that disturbed me greatly (see below).

A common trap, the knight is pinned but the pin is relative

rather than absolute. The sham sacrifice of the bishop on

f7 allows a recapture with check, a small material win and

a bigger positional advantage.

Jessie’s record of a blitz tournament at Coulsdon shows her winning a game against “her Hitler”, but the draw was changed, and we didn’t play that day.

This document would mean nothing to anyone else in the world, literally; this is far from the first time something like this has happened to me, which leads this lifelong atheist to believe there is some higher power or some higher something guiding his way through this life. This document records Jessie’s performance from a Blitz tournament held at her home club, Coulsdon, and it shows her beating me, her Hitler, for the first time.

The only problem with this score is that it is wrong. I remember this very well, because at the time she came up to me and said rather apprehensively that we had been paired against each other. Shortly after that, the draw was changed, so we didn’t play. Both of us ended up winning prizes, but not at the expense of the other.

After finding this document, I tried to ignore it, then rationalise it, perhaps she had made a mistake? This document was for her own personal use, and would never have been placed in the public domain, although maybe 40 or 50 years down the line when Nobel Prize winning research scientist Jessie Gilbert Phd was writing her memoirs, the tall dark man with a moustache she had fantasised about as a mercenary might figure as a footnote in her multi-volume autobiography.

Try as I may, I couldn’t ignore it, if Jessie could deceive herself about something so trivial, what else might she deceive herself about? Finally, after much research including in specialised medical textbooks, I managed to work out what had happened.

Ian Gilbert had been a bad father and a worse husband. At the time Jessie made these allegations, he had been evicted from the family home, all this came out at the trial and can be reported freely, but my access to the case papers confirmed what I had come to suspect.

On Friday, January 17, 2003, thirteen days short of Jessie’s sixteenth birthday, Ian Gilbert’s temper flared at the family home over a triviality. Jessie was on crutches after an operation on her left foot, and this evening, the family computer being off-line, he wanted to use her laptop. She was apprehensive about this – read between the lines – and he ended up trying to strangle her. The police were called, and he fled the family home. Although he was arrested later, he was not charged for what was a serious assault and could have been far worse. There must be special rules for bankers as well as for police officers.

This incident led to an acrimonious divorce. Although Ian Gilbert was granted access to his daughters, none of them wanted to see him, but something strange happened to Jessie. This is only speculation but intelligent speculation nevertheless, she turned the man who had nearly strangled her into a monster who raped her in her bed. I have no doubt that the failure to charge him with assault was a factor in this.

Two months after what was to become known as the computer incident, Jessie told a fellow chess player, Joseph Redpath, that she had been repeatedly sexually abused by her father. On May 14 the following year, she went out drinking heavily with a group of friends, and told them the same thing.

The following day she was admitted to East Surrey Hospital after taking an overdose of Paracetomol; this was a genuine suicide attempt and not one of those cries for help we hear so much about. She would say later that she wanted oblivion, and being an atheist like me, she realised there was only one way she could obtain it. Jessie’s overdose led to a police investigation, to her death aged only 19, and to the trial. Although an open verdict was returned at her inquest at Epsom in September the following year, there is no doubt that Jessie threw herself from that window rather than simply fell. The big question is, who pushed her?

There were in my humble opinion, three contributing factors. One was Ian Gilbert’s behaviour towards her and more generally his family. The second was those who fostered Jessie’s delusions instead of seeing them for what they were. Finally, there were the legal authorities, the police and more especially the CPS who in the first instance should have charged Jessie’s father with the original non-sexual assault. They were also both at fault for failing to investigate and assess Jessie’s claims with the proper critical faculty. Once Jessie had made her allegations formally, the police investigated, and for them it was a black and white situation, either she was lying or her father must be. Having been satisfied that she was sincere, there was nothing left but to charge him. They were though overlooking a third option that should have been every bit as obvious, Jessie could have been totally sincere, but delusional. As she was known to suffer from night terrors, this is something any experienced investigator should have considered.

I don’t want to take too much of a diversion here, but one of the most bizarre phenomena of the modern age is the rise in reports of alien abductions. Some studies indicate that millions of Americans actually believe they have experienced this, with the usual caveat about statistics and opinion polls. Can this be true? Of course not, so what is going on? The simplest explanation is something known as Old Hag Syndrome, or sleep paralysis. In days of yore, people would see demons and the like. For those who experience it, which is surely all or most of us at some time, it can feel like a demon, or an old hag, sitting on our chests. In extreme cases, it can be terrifying; women have been known to confuse it with rape. It is too well documented to discuss here the effects certain drugs can have on the mind, both conscious and unconscious. Some, like Pregabalin, can cause bizarre dreams.

Two well known examples of extreme cases of this phenomenon are the author Whitley Strieber, whose book Communion was passed off on the general public as a true account of his actually being kidnapped by aliens, and the rock musician Sammy Hagar, whose song Silver Lights was inspired by his experiences of sleep paralysis as a boy.

Anyone who finds this explanation unconvincing should study the works of Elizabeth Loftus with particular reference to false memories; for those who have shorter attention spans, here is a good place to start.

At his trial, Ian Gilbert suggested that Jessie had planned the rape allegations as part of a conscious strategy, he actually claimed she had been playing chess against him.

If Jessie had been an imbecile, like the young girl whose tall stories took in the gullible David Icke, that would have been plausible, but this was a girl who went on to win a place at Oxford University.

Even if Jessie had been the sort of person who would do that – and she wasn’t, take it from me – it would have been much easier for her to claim simply that he had molested her, as has sadly often happened in cases where fathers and their children (of both sexes) become estranged, especially where there is a history of violence.

If she had done that, we would have been in a classic situation of she said/he said, the frightened little woman and the beast. Jessie would not have needed to persist with these allegations, she could have cried off from a trial and left the mud to stick, no smoke without fire and all that.

The fact that she didn’t, and that she was clearly terrified of facing him indicates that for her, the rapes were real. The computer incident was a very obvious trigger, but not one of our so bright detectives appeared to do any detecting. As I know from personal experience, they seldom do, instead they find or are handed some evidence on a plate, perhaps a single witness statement which they don’t even bother to check, and even though it may contain several readily disprovable facts, they run with that, often hoping to pressurise some poor sap into confessing to a crime that may not have happened, or that may have been committed by someone else.

If a young girl tells you as a police officer in all sincerity that she has been abducted by aliens, what do you do? Laugh? Send her for counselling? If she tells you she has been raped repeatedly by her father since she was eight years old, but has been too terrified to report it until now, that is an entirely different ball game.

If Jessie had made these allegations forty or fifty years ago, probably nothing would have come of them. Perhaps the police were more savvy then. Perhaps we all were. The following are extracts from Wigmore On Evidence, Volume 3, (1940).

From page 459: “Modern psychiatrists have amply studied the behavior of errant young girls and women coming before the courts in all sorts of cases. Their psychic complexities are multifarious, distorted partly by inherent defects, partly by diseased derangements or abnormal instincts, partly by bad social environment, partly by temporary physiological or emotional conditions. One form taken by these complexes is that of contriving false charges of sexual offences by men.”

From page 461: “A motherless girl of 9½ years, following her complaint of local symptoms, which proved to be due to vulvitis, accused her father and brother of incest. She was a bright child and normally affectionate, even towards these relatives. Her father and brother were held in jail for several weeks, but were dismissed at the trial because of the ascertained untruth of the charges.”

In 1982, the BBC screened a fly-on-the-wall documentary that was to change the way the police investigate allegations of rape.

As one reviewer put it: “a woman with a history of psychiatric treatment claims she has been raped by three strangers and is, in turn, bullied and cajoled by three male officers who dismiss her story out of hand...Transmitted soon after an infamous court decision (in which a judge had accused a hitchhiker of contributory negligence in her own rape)...[it] caused a public outcry and led to a change in the way police forces handled rape cases. Within months, a new rape squad of five female officers was formed in Reading.”

Since that documentary, Britain’s so macho police have become increasingly hamstrung by political correctness, not just in issues relating to rape, of course. Allowing for the apparently appalling way this woman was treated, I can’t help thinking that if Jessie had been subjected to the same treatment, bullied, humiliated and ridiculed, she might have come to her senses. Certainly if the police had done their job thoroughly, they would have realised from the other evidence that the things she claimed her father did to her he couldn’t have done, not without someone else becoming aware of what was going on.

Instead, the girl who obviously needed some sort of psychiatric help was refused counselling because to do so would have undermined the prosecution of Ian Gilbert.

Understandably, not everyone was satisfied with the trial verdict; the statement that was read by Jessie’s mother after his acquittal was drafted by the Surrey Police press office.

Shortly after the trial, Angela Gilbert was arrested on suspicion of threatening to kill her ex-husband, although she suffered nothing more serious than spending a night in the cells. In July 2008, she was questioned after an apparently anonymous tip off that she had attempted to hire a hit man to kill him on the second anniversary of Jessie’s death. She branded the allegation ludicrous, as of course it was, though it is not unlikely that an attempt was made to entrap her in such a plot; the British police in particular have a long track record of seeking out people who have scores to settle, and then inciting them to commit criminal acts, usually conspiracy or incitement, which involves nothing more than enticing the intended victim into an unguarded or even a hypothetical conversation. As I know from personal experience. If the entrapment succeeds, some poor sap gets sent down; if not, they simply walk away and look for another mark believing, with good reason, that they and they alone are above the law. Regardless of this, it may be that someone working for Surrey Police still has a score to settle, though with him rather than with her.

Jessie Gilbert died a week before my 50th birthday. I wrote a short poem for her on that day. Exactly one year later, on my 51st birthday, I went to a seance, or what was meant to be a seance, at the Spiritualists Association. It was actually an audience with one of those evil people – a man in this case – who pose as bridges to the other side. 51 years old and a lifelong atheist, how crazy is that?

Shortly before Ian Gilbert’s acquittal, I had a surreal experience; on my first trip abroad for nearly 15 years, I was booked into an hotel and allocated a room on the 8th floor. As I looked down, I saw a similar scene to what Jessie must have seen in her last few seconds of life. She had fallen into a tree and become lodged in its branches. The trees below this window next to the elevator were pitiful things; if I jumped, I would have gone right through them. This terrible vision provided a moment of revealed truth for me, not the first I have had in my life, but to date by far the most significant.

For weeks and months I saw clones of Jessie everywhere I went. When a recent photograph was released after her death, I was astounded at the transformation. She hadn’t been blonde when I’d known her. In fact, when Jessica Laura Cory Gilbert was born in the Westminster Hospital, London, on January 30, 1987, her hair was black. She was named after Shylock’s wayward daughter in The Merchant Of Venice. It was an amazing transformation; although she had never been an ugly duckling, she had certainly blossomed into a beautiful swan.

Jessie’s chess had also improved dramatically . When she won the world title, she wasn’t that strong in absolute terms, for a girl of her age, but not as a player per se.

The following probably won’t mean much to non-chess players; they are British Chess Federation grades as credited:

GRADING LIST 1998-99, page vii: under TOP TWENTY GIRLS UNDER 18, Jessie is 15th, at age 11 and grade 116.

At page 7 we find BARON ALEX = 145; previous grade 0, ie inactive I made sure they corrected the name the following year!

At page 49, Jessie’s previous grade is given as 91.

GRADING LIST 2000-2001, page xv: under TOP JUNIORS UNDER-14, Jessie at age 13 is graded 149.

GRADING LIST 2001-2002, at page ix: under TOP LADIES, Jessie is listed in 12th place at 172, way behind Harriet Hunt at 231.

Page x: under TOP JUNIORS UNDER – 16, Jessie at age 14 is 19th; Timothy Woodward at 189 is 9th.

Page xi: Jessie is listed as Top Girl age 14, presumably Under 18. 17 year old Sophie Tidman was 166 in 2nd place.

Page 67: Jessie’s Rapidplay is given as 156, her previous is given as 145.

The last two years of her life saw a massive increase in her playing strength; in December 2005, she beat Danny Gormally at her home club, Coulsdon. Gormally is currently ranked 13 of active players in England. Then, in February 2006, Jessie won the first international chess tournament ever held in South Korea, an event that was organised by Adam Raoof.

At just 19, she was probably still ten years away from her peak as a player, and that without mentioning her academic studies. She could really have done anything she wanted.

Returning to the clones, in September 2007, the Daily Mail published a photograph of 15 year old Rosemary Edwards, who had also tragically committed suicide; from a distance, the picture of her holding her dog could be mistaken for Jessie. Jessie even had a similar dog. Most striking though was one day when I was catching the Underground at Kings Cross, a girl of perhaps 19 was bounding up the escalator with a determined look on her face. She had long blonde hair, and was wearing jeans, as Jessie always did. I almost called out to her, but stopped myself in time.

Worse than the haunting by her clones, I kept thinking of reasons I should have contacted her; we had on occasion exchanged e-mails, once she sent me a rather interesting spoof on Windows, but as I had lost interest in chess, a man of my age corresponding with a girl more than thirty years his junior, well, do the math.

Most of all, I thought about our last game, if only I had won that, played that sham sac with the bishop and really rubbed her nose in it, perhaps she would have regarded me as “unfinished business” and decided to seek me out to settle the score with the only player she had never beaten in five starts, and one who was now way below her in class. Perhaps during the course of our game I would ask her how her studies were going, and tell her her father must be proud of her. She would make a cynical comment which I would pursue, then she would tell me about the rapes, and how she was thinking of ending it all, how she had already tried. I would then tell her about my own failed suicide attempt, and talk her out of it. It sounds nice, but of course it is a fairy tale; the truth is that when Jessie stepped out of that window into oblivion that terrible night in Pardubice, both the man she had once affectionately referred to as her Hitler, and even the game she loved so much, were the very last things on her mind.

Jessie planned her suicide well in advance. That night, she plied her fourteen year old roommate with drink until she became physically sick, to get her out of the way. Jessie was not the sort of person who would have done that under any other circumstances, but she needed to be alone to carry out the dreadful deed.

When the police arrived, they found the room had been trashed, and not unnaturally suspected foul play, but Jessie had obviously done this, needing to psyche herself up, to find the courage. All this came out at the inquest. If only she hadn’t been so brave.

My endearing memory of Jessie is from shortly after we first met. Over the weekend of December 13/4, 1998, I played in a small congress in North London. It was only 5 rounds, and I scored a creditable 3 points, although one of my wins was a colossal swindle against Harvard graduate and distinguished Cambridge academic John Daugman.

Towards the end, I ran into Jessie in the corridor, and we exchanged hellos. She had been playing in one of the junior events and had scored 3½ out of 6. “I’m top girl”, she said with a slight smile and the air of satisfaction of a job well done.

I had hoped to pick up a prize in this tournament, but my remarkable winning streak which had begun with my taking first prize in four Minor Tournaments in a row had already come to an end, so having played and beaten Jessie twice by that time, I consoled myself with the thought that I was probably a stronger player than any 11 year old girl in London and the Home Counties. Six weeks later, she was thrust into the limelight after her historic win at Hastings.

That is how I will always remember her, and love her, as everyone who ever met Jessie loved her, however slightly they knew her. She will be my top girl as long as I live, and as only the good die young, that may be for some considerable time.

[The above was published originally December 14, 2011. It is republished here with some very minor alterations/corrections.]

Back To Digital Journal Index

A classic depiction of Old Hag Syndrome. It

may also manifest, in this modern age, as alien

abductions, or as terrifyingly real hallucinations

of rape.